Thinking About Higher for Longer

Having grown accustomed to free and freely available capital, it is not at all clear that the low interest rate environment of the past twenty years will return.

I was hoping to write a shorter, lighter and easier-to-digest Investment Insights this month. Coming after a three-part series on Volatility, Compounding and Asset Allocation – all very long, very serious and very technical discussions – I think we could agree that both reader and writer needed the break. However, current events have conspired against our shared interest in a light, late-summer perusal.

Equity markets have been under pressure in August, falling almost 5% at one point, from a subtle shift in market sentiment worth commenting on. Throughout the Federal Reserve’s rate-hiking campaign, investor attention has been focused first on how high interest rates would need to go to control inflation and then on how quickly thereafter, and how far, interest rates would fall.

The first question has been answered largely as expected. The Central Bank hiked interest rates for what could be the final time on July 26th. The second and third questions, however, remain unanswered. While investors have long hoped “soon” and “far” would prove correct, in recent weeks market sentiment has shifted toward “maybe not as soon” and “maybe not as far” as previously thought. Though subtle, this shift is important enough to the purposes of protecting and building wealth to abandon existing plans in favor of a timely discussion.

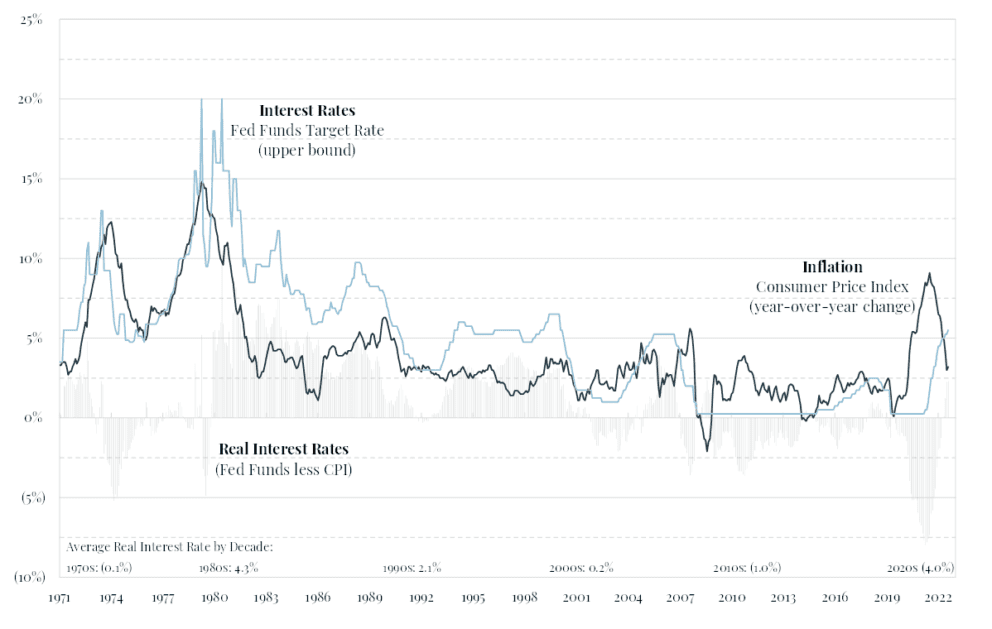

First, some historical context. When the Fed started raising interest rates last year, it ended a twenty-year period of expansionary monetary policy that featured 0% nominal interest rates, negative real interest rates and $9 trillion of Quantitative Easing. The chart below shows how historically anomalous this period was. The key takeaway is that for two decades the economy had grown accustomed to free and freely available capital and investors had become conditioned to Fed support for high asset prices.

Given recent and prolonged experience, it is certainly understandable that investors would expect interest rates to return to very low levels after the current bout of inflation is squashed. However, investors are now opening their minds to the possibility that maybe interest rates won’t be going back down for a while and won’t be going down as far once they do. This shift, to “higher for longer,” has far-reaching implications.

Why might this shift be happening? Among many factors, long-term interest rates reflect expectations for future inflation and economic growth. Strong economic growth this year, despite rising interest rates and stubborn inflation, has raised concern that higher long-term rates could be necessary. For the current quarter, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow estimate is 5.8%. If correct, this would be the strongest such figure since the third quarter of 2003 (excepting the post-pandemic reopening period), despite interest rates at a supposedly restrictive level.

This dichotomy is spurring some economists and investors to update their estimate of something called r* (pronounced “R-star”). r*, which can only be estimated, not observed, is the hypothetical neutral real rate of interest that neither slows nor accelerates the economy. Over the last two decades, estimates of r* had generally fallen due to globalization, geopolitical stability and demographic tailwinds. Now, with strong economic growth despite restrictive monetary policy, deglobalization, geopolitical instability and demographic headwinds, some Fed officials are beginning to speculate that the current consensus for r* is too low.

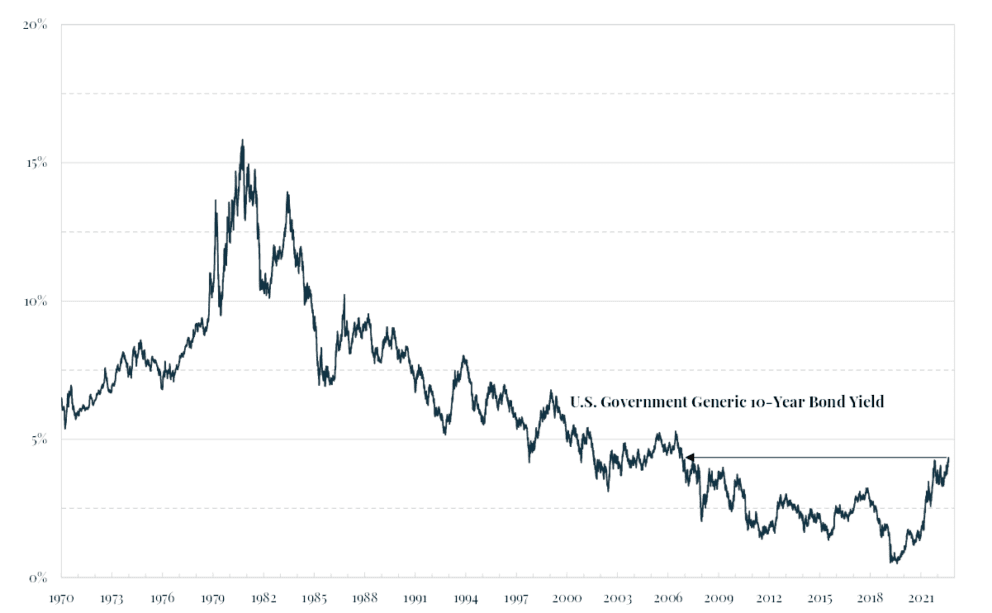

There are more practical factors driving this shift as well. When the Fed stopped buying treasury bonds in March 2022, one very large, price insensitive buyer left the market (less demand). This happened as rising government deficits were driving the issuance of large amounts of treasury bonds (more supply). With less demand and more supply, economics dictates that treasury bond prices had to fall. As prices fell, yields (interest rates) increased.

Why do long-term interest rates matter? The short answer is that long-term interest rates affect just about everything in the world of finance, which then in turn affects a wide range of real-world behavior. These changes can have profound and lasting implications, both mathematical and psychological.

The mathematical implications are straightforward. Higher interest rates mean that the present value of future cash flows is less than it was before. Conversely, current cash flows are less affected and become relatively more valuable. At the margin, this should shift investor preferences from speculative, often fast growing, but money losing businesses toward profitable businesses that are currently generating cash flow, reducing the price of the former and increasing the price of the latter.

TINA dies as well. TINA, fortunately not a real person, is an acronym for “there is no alternative” used during the extended period of low interest rates to describe investors’ reluctant purchase of equities to achieve a required rate of return when they would otherwise prefer to purchase bonds if interest rates were higher. With rates higher now, some investors will gladly sell equities and go back to bonds to achieve their required rate of return, putting downward pressure on equity prices.

More broadly, equity valuations should decline. As the yield on treasury bonds rises, a return considered to be risk-free, the earnings yield on equities, which reflects a risk premium over the risk-free yield, should rise as well. As the earnings yield on equities rises, equity prices must fall (all else equal).

In the real world, higher interest rates will mean a higher cost of capital for businesses, which will translate into a higher required rate of return on investments. All else equal, this should slow business investment.

Higher interest rates will also reduce corporate earnings as interest expense increases. Interest expense will increase as floating rate debt reprices higher and as outstanding debt is refinanced at the now-higher prevailing interest rate.

Consumers’ cost to borrow money will increase as well. This will make any type of large purchase that is typically financed, cars and homes being prime examples, more expensive as well as make it more costly to carry a revolving credit (i.e. credit card) balance. Anyone in the unenviable position of trying to buy a home knows this well, with mortgage rates recently hitting a 20-year high.

The psychological implications are more abstract, but no less real. Higher long-term interest rates can have a negative impact on risk taking, above and beyond simply making it more expensive to do so. The “animal spirits” in the market that you often hear about tend to quiet or go silent altogether during such times. Perhaps safety is simply seen as more rewarding for the moment. If not explicitly caused by higher long-term rates, the phenomenon is certainly correlated.

Falling asset prices, as mathematically outlined above, can sometimes cause the “wealth effect” to wane or reverse. The wealth effect suggests that people tend to spend more money when rising asset prices make them feel wealthier. The reverse holds true as well. When asset prices fall, people tend to spend less money. This does create the risk of a negative feedback loop emerging, whereby falling asset prices due to psychological reasons cause spending to slow, which in turn causes asset prices to fall further still, this time due to fundamental reasons, which then cause spending to slow further still and so on and so on.

We haven’t seen long-term interest rates this high in fifteen years. Since then, we have grown accustomed to low interest rates as normal. While it is natural to extrapolate the future from the recent past, it is not at all clear that we will go back to the low interest rate environment of the past twenty years.

Whatever the new normal, adjusting to it will take time and surprises will emerge along the way. Silicon Valley Bank, for example, was decidedly unprepared for a higher interest rate environment and failed because of it. Similarly, though lesser well known, many U.K. pension funds suffered a liquidity crisis in late 2022 as interest rates increased, only to eventually be bailed out by the Bank of England.

These two examples show the danger of optimizing for a particular environment rather than remaining flexible enough to survive in any environment. This is paralleled in biology. The evolutionary process is described as “survival of the fittest.” Read those four words carefully. It does not say survival of the “best.” As you think about protecting and building wealth over time, your goal should not be to be the best in a particular environment (or period of time as it applies to investing), but rather to survive well enough over time in any type of environment to allow the benefits of long-term compounding to accrue.

Thoughts? I would love to hear them. Email me at investmentinsights@zuckermaninvestmentgroup.com.

Written By Keith R. Schicker, CFA