It’s All Relative

How can good news sometimes be bad and bad news sometimes be good?

Sometimes all is not as it seems. I begin this column with the same words that I ended the last. However, the conundrum at hand today is much broader. Why do financial markets sometimes interpret good news as bad and bad news as good?

This dynamic appears widely and variously in markets, but most obviously with the reaction to the monthly Employment Situation report issued by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The month-to-month change in non-farm payrolls detailed therein is one of the most important pieces of economic data for financial markets. Everyone watches closely. Roughly 70 economists from around the world formally attempt to predict this figure and an untold number of market participants make informal guesses, often implicitly as they seek to profit from changes in asset prices caused by the report.

When the actual results exceed the average of all formal estimates, the outcome is generally described as strong or good. Logically, markets rise in response. This was the case back in May 2020, when the economy added 2,509,000 jobs against expectations for a loss of 7,500,000 jobs. Markets cheered the result, climbing almost 3% on the news.

Markets sometimes defy logic though. Take January 2023 for example. Employment grew by 517,000 jobs from December, nearly thrice the expected tally of 189,000. Markets were obviously pleased, right? Well, as it turns out, they were not and declined 1% on the news.

When actual results fall short of the consensus, the outcome is generally characterized as weak or bad. Logically, markets fall in response. This was the case back in February 2019. Non-farm payrolls rose by 20,000 jobs, a small fraction of the expected advance of 180,000 jobs. Left disappointed, the market slipped modestly on the day.

Paradoxically though, sometimes bad news is just what markets want to hear. Back in May 2019, non-farm payrolls grew by only a meager 75,000 jobs, far below the 175,000-job consensus. Strangely, markets rejoiced, rising more than 1%.

This dynamic happens because markets are a not just a scoring tool, reacting to events as they happen, they are also a prediction tool and conversion tool, continuously forming and updating forecasts of what is expected to happen in the future and transforming those forecasts into a present-day dollar value. Every moment of every day, untold numbers of market participants are deciding to buy, sell or do nothing based on their most current expectations for the future. The collective sum of all these decisions is then anthropomorphized as “the market” as if it had a will of its own.

While the market does care about what has happened, it cares far, far, far more about what will happen. Regardless of whether something that happens is better or worse than what was expected to happen, that information will be received either positively or negatively based on how it affects expectations for what will happen going forward. A business could report absolutely abysmal financial results for the just-completed period, but if it also announces that it has just discovered cold fusion you can bet that the stock would move higher in response.

Markets are in fact so skilled at this process that they will often also predict and incorporate second and third order effects that may now happen due to a piece of new information. A good example of this would be the market’s reaction to the GLP-1 weight loss drugs. Obviously, the pharmaceutical companies that produce these drugs have seen their stock prices rise (first-order effect), but medical device manufacturers and consumer packaged goods companies have seen their stock prices fall (second-order effect) over fears of possibly lower demand (fewer heart attacks and less junk food, respectively) and the money that would have been spent on those items will be reallocated elsewhere across the economy (third order effect).

This also explains why markets do not move smoothly in a single direction for long. Strong results change the very structure of market itself, continuously raising expectations for what is to happen in the future until the bar is eventually too high to clear and disappointment results. Weak results work similarly, eventually moving the bar so low it would be impossible to fall short.

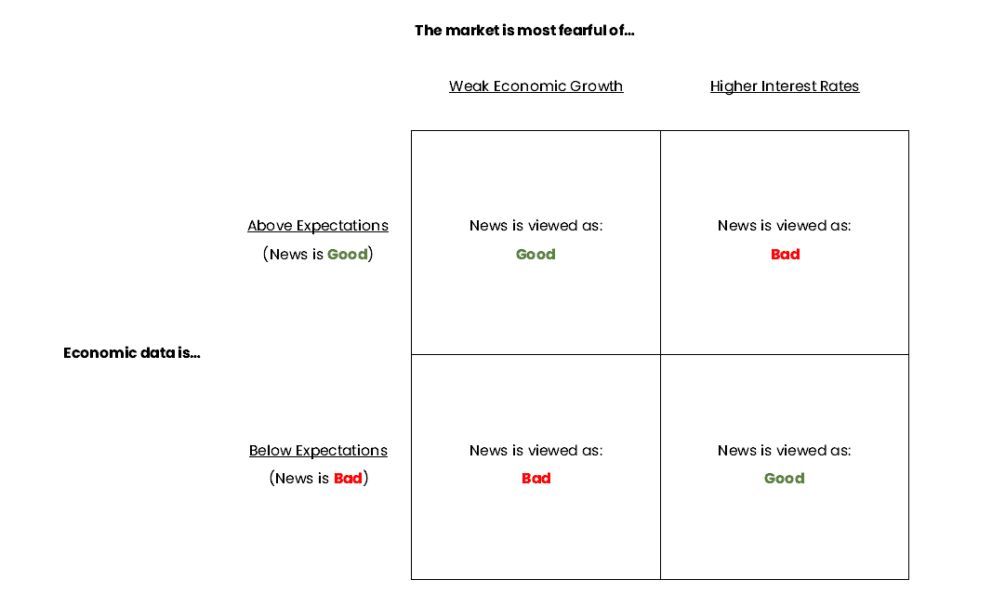

Returning specifically to the oft-contradictory non-farm payrolls example above, two assumptions are required to explain how things sometimes get turned upside down: Markets love growth and hate high interest rates. Growth drives earnings higher over time, which in turn drive equity prices higher. High interest rates are simply the antithesis of growth. So, any data that shows accelerating growth are welcomed. Any data that points to higher interest rates are not.

Determining whether good or bad economic data will be received positively or negatively depends on determining what the market is most fearful of. If the market is most fearful about economic growth, then good news is in fact good to hear (because the economy is stronger than thought) and bad news is in fact bad (because the economy is weaker than thought).

Things get turned upside down though when the market is most fearful about higher interest rates. Then good news is bad to hear (because the strong economy will lead to higher interest rates) and bad news is good to hear (because the weak economy will lead to lower interest rates). This is more-or-less the position that markets are in right now: Fearful that the resilient economy may lead the Federal Reserve to increase interest rates further still.

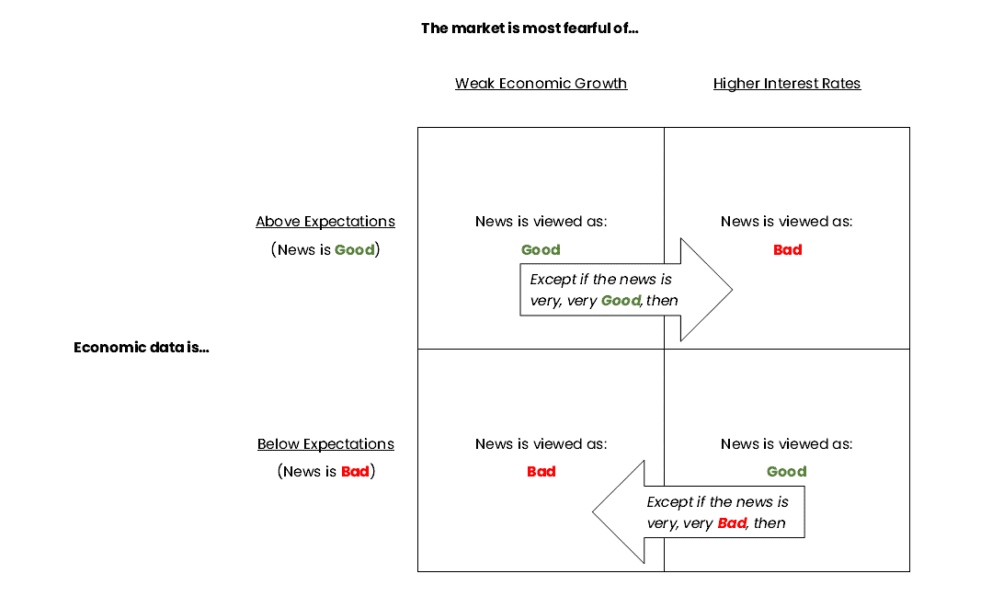

This framework, though exceedingly elegant and simple, is ultimately made fragile by the shifting sands of the market. First, you need to know what the market is most concerned about at any given point in time. As we learned above, there is no “market” to answer your query so this can be difficult to know confidently short of asking all of the individual participants. Worse yet, given the constant release of economic data and other market-moving information, it is not unthinkable that the market’s primary concern could change back and forth several times within the same week or month.

Even if you could know the market’s primary concern accurately and in real-time, it gets even more complicated still. If the market is fearful of higher interest rates, bad news that would normally be received positively could be met coldly if the bad news is so very bad that it changes the market’s primary concern to economic weakness. Likewise, if the market is concerned about economic weakness, good news that would normally be encouraging could become discouraging if the good news is so very good that it changes the market’s primary concern to higher interest rates.

There are certainly many other exceptions to this framework and likely as many nuances as there are market participants. Markets are, by their very nature, dynamic and always shifting. Patterns and behavior relied upon in this analysis could have already changed between the time that I wrote this and the time that you read this. As is often said, do your own due diligence.

Saying that you would need a crystal ball to predict the market is incorrect. The market itself is the crystal ball, albeit a murky, erratic, inconsistent and amorphous crystal ball, ever trying and ever failing to accurately predict the future. This is how, in the words of Lewis Carroll’s Mad Hatter, “Nothing would be what it was, because everything would be what it isn’t. And contrary-wise, what is, wouldn’t be. And what it wouldn’t be, it would. You See?”

The way to protect and build wealth over time, then, is to simply refuse to play the game. Ignore the day-to-day ups and downs of the market, disregard the headlines purporting to explain every move and remain resolutely focused on the long-term. Focus on the underlying fundamentals, use short-term volatility to your advantage and trust that success will necessarily follow.

Thoughts? I would love to hear them. Email me at investmentinsights@zuckermaninvestmentgroup.com.

Written By Keith R. Schicker, CFA